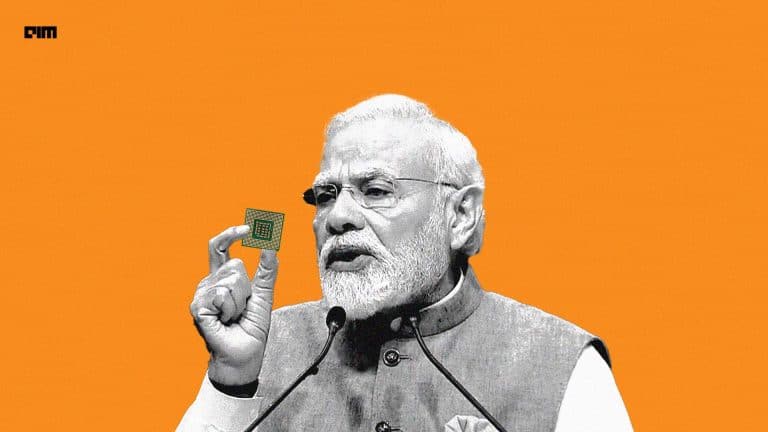

India has grand ambitions in the semiconductor space. Last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi urged the industry to make India a global hub for semiconductors. However, as it appears, India’s semiconductor aspiration is in total disarray.

Last year, in a landmark decision, the Indian government launched the production-linked incentive (PLI) and sanctioned INR 76,000 crore to encourage semiconductor manufacturing in India. Pretty soon, Indian billionaire Vedanta’s Anil Agarwal grabbed headlines as his venture tied up with Taiwanese company Foxconn to build a chip manufacturing plant in Dholera, Gujarat, on 400 acres of land.

However, a recent Bloomberg report suggested that the Indian government will not incentivise Agarwal’s chip venture, dealing a blow to the billionaire’s aspirations of establishing India’s version of Silicon Valley. According to the report, Vedanta’s application for government assistance seeking substantial funding, did not meet the government’s criteria. Moreover, the project is still in the process of finding a technology partner and acquiring a manufacturing-grade technology licence to develop 28nm chips.

Surprisingly, or coincidentally, a day after the report, the government announced in a press release that they will be accepting new applications for the establishment of semiconductor and display fabs in India starting June 1, as part of the Modified Semicon India Programme.

Back to square one

The India Semiconductor Mission (ISM) was launched with great anticipation in 2021 to drive growth of the industry in India. However, as it appears, we are back to square one. “The delays and inefficiencies in communication and processing have resulted in the loss of one-and-a half-years,” Arun Mampazhy, semiconductor analyst, told AIM.

Previously, three applicants — Vedanta-Foxconn JV, IGSS Ventures, and ISMC — submitted proposals to set up semiconductor fabs. However, for different reasons, it appears unlikely that anyone of the three applicants will be making semiconductors in India anytime soon.

“IGSS Ventures was not able to show a proper technology licence for 28nm chips and the ISM also asked them to get a strong Indian business partner. Even though it’s nowhere written in the policy, it kind of makes sense for India to ask for a strong Indian business partner,” Mampazhy said.

When it comes to ISMC, which is a joint venture between United Arab Emirates-based investment firm Next Orbit Ventures and Israel-based Tower Semiconductor, the government is waiting for Intel’s acquisition of Tower Semiconductor to complete and to see whether Intel will approve the technology transfer.

As uncertainty looms in the air, Union Minister Rajeev Chandrasekhar took to Twitter to respond to the Bloomberg report. He said, “The first window for more expensive 28nm fabs was kept open for 45 days till January 2022. It received three applicants that were evaluated by ISM and its Advisory group. The strategy now is also encouraging mature nodes of 40nm — current and new players may apply afresh in various nodes that they have the technology for.”

However, when the scheme was first announced, it clearly mentioned that it can be availed by anyone making 28 nm chips — 28-45 nm chips and 46-65 nm chips. “It is uncertain whether the minister is unaware of the specific policy that was in place when the incentives were first announced one-and-a-half years ago, or if he is intentionally making misleading statements to downplay the failure,” Mampazhy said.

Even if it’s the truth, it is not the right way to proceed, Mampazhy emphasised. “It is messy. The government should have come out and said why the earlier applicants won’t be granted any incentives and that they can reapply under the Modified Semicon India Programme.

This could have legal repercussions

While it makes sense for the government to reopen the applications and request all to reapply. By doing so, they have ensured a fair and transparent process. However, letting the three applicants reapply could also have legal repercussions, according to Mampazhy.

“Similar situations have occurred in the past, such as the case with 2G licences several years ago. The criteria were continuously adjusted by the minister after the deadline, based on the specific applicants received. This kind of modification, done by the government, may raise concerns about fairness and eligibility for obtaining licences,” he said.

India Semiconductor Mission lacks leadership and vision

Given that more than a year-and-a-half after the PLI scheme announcement, we still don’t have any concrete development in the semiconductor space also raises questions about the leadership at ISM. To drive the mission, what it needs is someone who understands the nitty-gritties of the semiconductor industry. However, if we take a look at the top leadership of ISM, they have no background in the semiconductor space. “The CEO is a joint secretary of the Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY) and has absolutely no semiconductor background. The CTO is a scientist at MeitY and he too had no real exposure to the semiconductor industry throughout his career,” Mampazhy said.

Other leadership positions at ISM are also mostly filled by scientists from MeitY. In January 2022, reports came out suggesting that the government will hire someone with over 25 years of experience in the semiconductor industry and more than 10 years of experience at global level to serve as the CEO of ISM. But the fact that it has been more than 15 months now, does not bode well with India’s grand ambition. Mampazhy even questions the government’s dedication and seriousness towards making semiconductors in India.

The current situation appears to be a bureaucratic mess, reminiscent of India’s previous attempts to attract global semiconductor manufacturers, raising concerns about the success of the country’s semiconductor endeavour.

Back in 2005, the Indian government tried to attract semiconductor manufacturing giants to set foot in India; however, unfavourable business conditions and bureaucratic hurdles drove them away. India made similar attempts to lure chipmakers in the following years as well without success. Nonetheless, India is in a much better position now, when compared to 2005. Last year, Tata Sons chairman Natarajan Chandrasekaran also confirmed their much-anticipated entry into the semiconductor space.

“To drive India’s semiconductor mission, the government needs to prioritise focus, vision, and strong leadership. It should streamline decision-making processes, ensuring efficiency and promptness,” Mampazhy said.